A Stray Bullet (Death in Gaza, Everyday)

(inspired by the talk given by poet and scholar Refaat Alrareer)

A father,

outside buying food for his young children,

A sudden shot fired,

at the market-place where the father was,

that stray bullet hitting an unintended target

the food dropping from his hands

scattering over the floors of the marketplace

mingling together with the blood seeping out from him.

Such a small thing,

yet so fatal,

in the wrong hands,

spells death for the innocent

coming to anyone,

anywhere,

anytime...

Thursday, 24 October 2013

Wednesday, 23 October 2013

War Poetry: World War 1 to Contemporary War Poetry

War Poetry: World War 1 to Contemporary War Poetry

The Battle Hymn of the Republic

by Julia Ward Howe

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps;

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read his righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on.

I have read a fiery gospel, writ in burnished rows of steel:

"As ye deal with my contemners, so with you my grace shall deal;

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel,

Since God is marching on."

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before his judgment-seat:

O, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my feet!

Our God is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me:

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

Poets have written about the experience of war since the Greeks, but the young soldier poets of the First World War established war poetry as a literary genre. Their combined voice has become one of the defining texts of Twentieth Century Europe.

In 1914 hundreds of young men in uniform took to writing poetry as a way of striving to express extreme emotion at the very edge of experience. The work of a handful of these, such as Owen, Rosenberg and Sassoon, has endured to become what Andrew Motion has called ‘a sacred national text’.

Although ‘war poet’ tends traditionally to refer to active combatants, war poetry has been written by many ‘civilians’ caught up in conflict in other ways: Cesar Vallejo and WH Auden in the Spanish Civil War, Margaret Postgate Cole and Rose Macaulay in the First World War, James Fenton in Cambodia.

In the global, ‘total war’ of 1939-45, that saw the holocaust, the blitz and Hiroshima, virtually no poet was untouched by the experience of war. The same was true for the civil conflicts and revolutions in Spain and Eastern Europe. That does not mean, however, that every poet responded to war by writing directly about it. For some, the proper response of a poet was one of consciously (conscientiously) keeping silent.

War poetry is not necessarily ‘anti-war’. It is, however, about the very large questions of life: identity, innocence, guilt, loyalty, courage, compassion, humanity, duty, desire, death. Its response to these questions, and its relation of immediate personal experience to moments of national and international crisis, gives war poetry an extra-literary importance. Owen wrote that even Shakespeare seems ‘vapid’ after Sassoon: ‘not of course because Sassoon is a greater artist, but because of the subjects’.

War poetry is currently studied in every school in Britain. It has become part of the mythology of nationhood, and an expression of both historical consciousness and political conscience. The way we read – and perhaps revere – war poetry, says something about what we are, and what we want to be, as a nation.

Poetry of war

Poetry of war is of two kinds: poetry written about war by poets who may or may not have direct experience of it and poetry written by soldier-poets. The latter are very much a 20th-century phenomenon as whole societies were mobilized for total war. But poems about war are as old as poetry itself, beginning with the greatest poem in European culture, Homer's Iliad composed in the 8th century bc telling the legendary tales of Troy and war between Greek and Trojan.

As the features of modern ‘industrial’ war became discernible in the 19th century, so contemporary poets tried to clothe them in classical respectability. Tennyson's ‘six hundred’ were a modern-day equivalent to the Spartans at Thermopylae save that ‘someone had blundered’ and their sacrifice was unintentional. The fratricidal bloodshed of the American civil war was mourned by James Lowell and Walt Whitman. Time brought reconciliation and death united enemies, but as Julia Howe put it in The Battle Hymn of the Republic, God's purpose remained ‘to make men free’ after Christ's example.

Poets began to accept that war might be worth it when the cause was justified, which explains why the outbreak of war in 1914 was greeted with such apparent enthusiasm in verse. Rupert Brooke was not alone in seeing war as a consummation and it misrepresents his individual and often ironic poetry to view it as the result of naïve and youthful innocence. What is more, his generation, throughout Europe, had been prepared beforehand to describe their sentiments in poetic form. Catherine Reilly has identified details of 2, 225 published poets in English during this period. This can be matched by enormous poetic output across Europe. The nature of modern conscripted mass armies which faced each other provided the reason why it is WW I which sees the specific coining of the phrases ‘war poet’ and ‘war poetry’, as Robert Graves points out, himself one of the foremost ‘poets in arms’. On all sides soldier-poets could be found; men and women in the ranks (including army, navy, air, and support services) who were themselves poets or who used poetry as a medium for expression, as distinct from civilians who only wrote poetry about the war. The most famous and moving of the latter was W. B. Yeats.

A familiar list of British poets was given critical acclaim, mostly after the war, in the framework of a developing critique which saw a transition from youthful innocence in 1914 to knowing and outright condemnation in 1918. Beginning with Brooke, the roll passes through Robert Graves, Edmund Blunden, and Siegfried Sassoon, and ends with Isaac Rosenberg and Wilfred Owen. Of these, only the middle three lived to tell the tale and could only escape from their post-war reputations in various forms of self-imposed exile. The public taste for ‘war poets’ was insatiable, especially for published collections of poets who had fallen in the war.

Their work had an oracular or prophetic immediacy for a civilian population generally starved of real news about the war. More recently, other poets have been ‘discovered’ and admitted to the roll, such as Edward Thomas and Ivor Gurney. Other European powers also produced war poets in their own right who became involved in the war. These included George Trakl and Yuan Goll writing in Germany, Guillaume Apollinaire in French, and Giuseppe Ungaretti and Gabiele d'Annunzio in Italian. It is possibly the nature of the war on the western front which produced such a volume of war poetry. The eastern front produced far less although the Russian poet Valery Brysov, working as a war correspondent, wrote a good deal. Other Russian war poets were Nikolai Gumilev and Velemir Khlebnikov. Russian poetry tended to the apocalyptic and visionary rather than preoccupation with the blood and ruin of the real war.

So strong was the desire for the insights of the soldier-poet that it inspired new outpourings in the 1930s during the Spanish civil war and, at the beginning of WW II, the question ‘where are the war poets?’ was answered in work of at least as high a standard as that of Owen and Sassoon, including the poetry of Keith Douglas, Alun Lewis, Frank Thompson, John Pudney, Henry Reed, and Alan Ross, to select only a small number. WW II produced little poetry of suffering in the West perhaps because of its nature, perhaps because it was seen as a ‘good war’. The greatest volume of poetry in this war came from the country which suffered most: Russia, notably the poetry of Anna Akhmatova and Aleksey Tvardovsky.

The lasting achievement of the ‘war poets’ in the 20th century is that they demonstrated that poetry should not follow blindly the political causes of the moment, should not serve the state or provide the new rallying cries, but should remain critical. Poetry about war since 1945 has embraced this rich and diverse legacy. From the therapeutic and popular poetry of Vietnam veterans, to be found in profusion on the internet, to the mannered criticisms of the Cold War and beyond in the work of the Liverpool Poets and Bob Dylan, or to the lyricism of Seamus Heaney's Requiem for the Croppies, the democratization of war poetry is sadly a reflection of the scale, frequency, and universality of the experience of war in our time.

http://www.warpoets.org/articles/what/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_poet

The Battle Hymn of the Republic

by Julia Ward Howe

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps;

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read his righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on.

I have read a fiery gospel, writ in burnished rows of steel:

"As ye deal with my contemners, so with you my grace shall deal;

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel,

Since God is marching on."

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before his judgment-seat:

O, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my feet!

Our God is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me:

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

Poets have written about the experience of war since the Greeks, but the young soldier poets of the First World War established war poetry as a literary genre. Their combined voice has become one of the defining texts of Twentieth Century Europe.

In 1914 hundreds of young men in uniform took to writing poetry as a way of striving to express extreme emotion at the very edge of experience. The work of a handful of these, such as Owen, Rosenberg and Sassoon, has endured to become what Andrew Motion has called ‘a sacred national text’.

Although ‘war poet’ tends traditionally to refer to active combatants, war poetry has been written by many ‘civilians’ caught up in conflict in other ways: Cesar Vallejo and WH Auden in the Spanish Civil War, Margaret Postgate Cole and Rose Macaulay in the First World War, James Fenton in Cambodia.

In the global, ‘total war’ of 1939-45, that saw the holocaust, the blitz and Hiroshima, virtually no poet was untouched by the experience of war. The same was true for the civil conflicts and revolutions in Spain and Eastern Europe. That does not mean, however, that every poet responded to war by writing directly about it. For some, the proper response of a poet was one of consciously (conscientiously) keeping silent.

War poetry is not necessarily ‘anti-war’. It is, however, about the very large questions of life: identity, innocence, guilt, loyalty, courage, compassion, humanity, duty, desire, death. Its response to these questions, and its relation of immediate personal experience to moments of national and international crisis, gives war poetry an extra-literary importance. Owen wrote that even Shakespeare seems ‘vapid’ after Sassoon: ‘not of course because Sassoon is a greater artist, but because of the subjects’.

War poetry is currently studied in every school in Britain. It has become part of the mythology of nationhood, and an expression of both historical consciousness and political conscience. The way we read – and perhaps revere – war poetry, says something about what we are, and what we want to be, as a nation.

Poetry of war

Poetry of war is of two kinds: poetry written about war by poets who may or may not have direct experience of it and poetry written by soldier-poets. The latter are very much a 20th-century phenomenon as whole societies were mobilized for total war. But poems about war are as old as poetry itself, beginning with the greatest poem in European culture, Homer's Iliad composed in the 8th century bc telling the legendary tales of Troy and war between Greek and Trojan.

As the features of modern ‘industrial’ war became discernible in the 19th century, so contemporary poets tried to clothe them in classical respectability. Tennyson's ‘six hundred’ were a modern-day equivalent to the Spartans at Thermopylae save that ‘someone had blundered’ and their sacrifice was unintentional. The fratricidal bloodshed of the American civil war was mourned by James Lowell and Walt Whitman. Time brought reconciliation and death united enemies, but as Julia Howe put it in The Battle Hymn of the Republic, God's purpose remained ‘to make men free’ after Christ's example.

Poets began to accept that war might be worth it when the cause was justified, which explains why the outbreak of war in 1914 was greeted with such apparent enthusiasm in verse. Rupert Brooke was not alone in seeing war as a consummation and it misrepresents his individual and often ironic poetry to view it as the result of naïve and youthful innocence. What is more, his generation, throughout Europe, had been prepared beforehand to describe their sentiments in poetic form. Catherine Reilly has identified details of 2, 225 published poets in English during this period. This can be matched by enormous poetic output across Europe. The nature of modern conscripted mass armies which faced each other provided the reason why it is WW I which sees the specific coining of the phrases ‘war poet’ and ‘war poetry’, as Robert Graves points out, himself one of the foremost ‘poets in arms’. On all sides soldier-poets could be found; men and women in the ranks (including army, navy, air, and support services) who were themselves poets or who used poetry as a medium for expression, as distinct from civilians who only wrote poetry about the war. The most famous and moving of the latter was W. B. Yeats.

A familiar list of British poets was given critical acclaim, mostly after the war, in the framework of a developing critique which saw a transition from youthful innocence in 1914 to knowing and outright condemnation in 1918. Beginning with Brooke, the roll passes through Robert Graves, Edmund Blunden, and Siegfried Sassoon, and ends with Isaac Rosenberg and Wilfred Owen. Of these, only the middle three lived to tell the tale and could only escape from their post-war reputations in various forms of self-imposed exile. The public taste for ‘war poets’ was insatiable, especially for published collections of poets who had fallen in the war.

Their work had an oracular or prophetic immediacy for a civilian population generally starved of real news about the war. More recently, other poets have been ‘discovered’ and admitted to the roll, such as Edward Thomas and Ivor Gurney. Other European powers also produced war poets in their own right who became involved in the war. These included George Trakl and Yuan Goll writing in Germany, Guillaume Apollinaire in French, and Giuseppe Ungaretti and Gabiele d'Annunzio in Italian. It is possibly the nature of the war on the western front which produced such a volume of war poetry. The eastern front produced far less although the Russian poet Valery Brysov, working as a war correspondent, wrote a good deal. Other Russian war poets were Nikolai Gumilev and Velemir Khlebnikov. Russian poetry tended to the apocalyptic and visionary rather than preoccupation with the blood and ruin of the real war.

So strong was the desire for the insights of the soldier-poet that it inspired new outpourings in the 1930s during the Spanish civil war and, at the beginning of WW II, the question ‘where are the war poets?’ was answered in work of at least as high a standard as that of Owen and Sassoon, including the poetry of Keith Douglas, Alun Lewis, Frank Thompson, John Pudney, Henry Reed, and Alan Ross, to select only a small number. WW II produced little poetry of suffering in the West perhaps because of its nature, perhaps because it was seen as a ‘good war’. The greatest volume of poetry in this war came from the country which suffered most: Russia, notably the poetry of Anna Akhmatova and Aleksey Tvardovsky.

The lasting achievement of the ‘war poets’ in the 20th century is that they demonstrated that poetry should not follow blindly the political causes of the moment, should not serve the state or provide the new rallying cries, but should remain critical. Poetry about war since 1945 has embraced this rich and diverse legacy. From the therapeutic and popular poetry of Vietnam veterans, to be found in profusion on the internet, to the mannered criticisms of the Cold War and beyond in the work of the Liverpool Poets and Bob Dylan, or to the lyricism of Seamus Heaney's Requiem for the Croppies, the democratization of war poetry is sadly a reflection of the scale, frequency, and universality of the experience of war in our time.

http://www.warpoets.org/articles/what/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_poet

A Date with a Literary Scholar : Refaat Alareer

A Date with a Literary Scholar : Refaat Alareer

History of Palestine

Palestine (Arabic: فلسطين Filasṭīn, Falasṭīn, Filisṭīn; Greek: Παλαιστίνη, Palaistinē; Latin: Palaestina; Hebrew: פלשתינה Palestina) is a geographic region in Western Asia between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. It is sometimes considered to include adjoining territories. The name was used by Ancient Greek writers, and was later used for the Roman province Syria Palaestina, the Byzantine Palaestina Prima and the Umayyad and Abbasid province of Jund Filastin. The region is also known as the Land of Israel (Hebrew: ארץ־ישראל Eretz-Yisra'el),the Holy Land, the Southern Levant, Cisjordan, and historically has been known by other names including Canaan, Southern Syria and Jerusalem.

Situated at a strategic location between Egypt, Syria and Arabia, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a long and tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region has been controlled by numerous different peoples, including Ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Ancient Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, the Sunni Arab Caliphates, the Shia Fatimid Caliphate, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mameluks, Ottomans, the British and modern Israelis and Palestinians.

Boundaries of the region have changed throughout history, and were last defined in modern times by the Franco-British boundary agreement (1920) and the Transjordan memorandum of 16 September 1922, during the mandate period. Today, the region comprises the State of Israel and the State of Palestine.

Famous Palestinian Poets (Written in Arabic)

- Mahmoud Darwish

- Tamim Bargouti

Famous Palestinian Poets (Written in English)

- Rafeef Ziadah (We Teach Life, Sir)

- Susan Abulhawa (Wala!)

- Remi Kanazi

Poetry: How it all started

1. Read a lot of good and high quality poetry

2. Believe you can write good stuff

3. Have the will to do so

4. Scribble your thoughts down. Always

5. Imitate

What is in my poetry?

- Dialouge

- Performance / Drama

- About Palestine

Questions that were asked by some of the students to the Scholar.

1. Who are your favourite poets and why?

Answer : John Donne

2. What was the style of poetry written before the war came to Palestine?

Answer : Personal poetry that was distinticve. It was pretty much the same style before the was began. Poetry became intense after the war broke out in Palestine.

History of Palestine

Palestine (Arabic: فلسطين Filasṭīn, Falasṭīn, Filisṭīn; Greek: Παλαιστίνη, Palaistinē; Latin: Palaestina; Hebrew: פלשתינה Palestina) is a geographic region in Western Asia between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. It is sometimes considered to include adjoining territories. The name was used by Ancient Greek writers, and was later used for the Roman province Syria Palaestina, the Byzantine Palaestina Prima and the Umayyad and Abbasid province of Jund Filastin. The region is also known as the Land of Israel (Hebrew: ארץ־ישראל Eretz-Yisra'el),the Holy Land, the Southern Levant, Cisjordan, and historically has been known by other names including Canaan, Southern Syria and Jerusalem.

Situated at a strategic location between Egypt, Syria and Arabia, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a long and tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region has been controlled by numerous different peoples, including Ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Ancient Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, the Sunni Arab Caliphates, the Shia Fatimid Caliphate, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mameluks, Ottomans, the British and modern Israelis and Palestinians.

Boundaries of the region have changed throughout history, and were last defined in modern times by the Franco-British boundary agreement (1920) and the Transjordan memorandum of 16 September 1922, during the mandate period. Today, the region comprises the State of Israel and the State of Palestine.

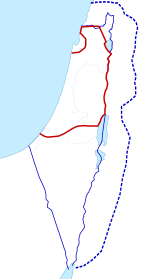

1916-22 Proposals: Three proposals for the post World War I administration of Palestine. The red line is the "International Administration" proposed in the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, the dashed blue line is the 1919 Zionist Organization proposal at theParis Peace Conference, and the thin blue line refers to the final borders of the 1923-48Mandatory Palestine.

1947 (Actual): Mandatory Palestine, showing Jewish-owned regions in Palestine as of 1947 in blue, constituting 6% of the total land area, of which more than half was held by the JNF and PICA. The Jewish population had increased from 83,790 in 1922 to 608,000 in 1946.

1947 (Proposal): Proposal per the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine(UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II), 1947), prior to the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The proposal included aCorpus Separatum for Jerusalem, extraterritorial crossroads between the non-contiguous areas, and Jaffa as an Arab exclave.

1948-67 (Actual): TheJordanian occupied West Bankand Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip (note the dotted lines between the territories and Jordan / Egypt), after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, showing1949 armistice lines.

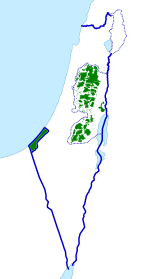

Current: Extant region administered by thePalestinian National Authority(under Oslo 2).

- Mahmoud Darwish

- Tamim Bargouti

Famous Palestinian Poets (Written in English)

- Rafeef Ziadah (We Teach Life, Sir)

- Susan Abulhawa (Wala!)

- Remi Kanazi

Poetry: How it all started

1. Read a lot of good and high quality poetry

2. Believe you can write good stuff

3. Have the will to do so

4. Scribble your thoughts down. Always

5. Imitate

What is in my poetry?

- Dialouge

- Performance / Drama

- About Palestine

Questions that were asked by some of the students to the Scholar.

1. Who are your favourite poets and why?

Answer : John Donne

2. What was the style of poetry written before the war came to Palestine?

Answer : Personal poetry that was distinticve. It was pretty much the same style before the was began. Poetry became intense after the war broke out in Palestine.

Thursday, 10 October 2013

What is Drama?

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action" (Classical Greek: δρᾶμα, drama), which is derived from the verb meaning "to do" or "to act" (Classical Greek: δράω, draō). The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception. The early modern tragedy Hamlet (1601) by Shakespeare and the classical Athenian tragedy Oedipus the King (c. 429 BCE) by Sophocles are among the masterpieces of the art of drama. A modern example is Long Day's Journey into Night by Eugene O’Neill (1956).

The two masks associated with drama represent the traditional generic division between comedy and tragedy. They are symbols of the ancient Greek Muses, Thalia and Melpomene. Thalia was the Muse of comedy (the laughing face), while Melpomene was the Muse of tragedy (the weeping face). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been contrasted with the epic and the lyrical modes ever since Aristotle's Poetics (c. 335 BCE)—the earliest work of dramatic theory.

Forms of Drama:

Opera

Western opera is a dramatic art form, which arose during the Renaissance in an attempt to revive the classical Greek drama tradition in which both music and theatre were combined. Being strongly intertwined with western classical music, the opera has undergone enormous changes in the past four centuries and it is an important form of theatre until this day. Noteworthy is the huge influence of the German 19th-century composer Richard Wagner on the opera tradition. In his view, there was no proper balance between music and theatre in the operas of his time, because the music seemed to be more important than the dramatic aspects in these works. To restore the connection with the traditional Greek drama, he entirely renewed the operatic format, and to emphasize the equal importance of music and drama in these new works, he called them "music dramas".

Chinese opera has seen a more conservative development over a somewhat longer period of time.

Pantomime

These stories follow in the tradition of fables and folk tales. Usually there is a lesson learned, and with some help from the audience, the hero/heroine saves the day. This kind of play uses stock characters seen in masque and again commedia dell'arte, these characters include the villain (doctore), the clown/servant (Arlechino/Harlequin/buttons), the lovers etc. These plays usually have an emphasis on moral dilemmas, and good always triumphs over evil, this kind of play is also very entertaining making it a very effective way of reaching many people.

Creative drama

Creative drama includes dramatic activities and games used primarily in educational settings with children. Its roots in the United States began in the early 1900s. Winifred Ward is considered to be the founder of creative drama in education, establishing the first academic use of drama in Evanston, Illinois.

My favourite playright

William Shakespeare was one of the first playrights I had began reading as a young child. I was introduced to classics like Romeo and Juliet and a little bit of King Henry VIII (the simplified version) while I was in primary school. Later I began reading more and more of his works that was not simplified and realized I had a love for the medieval dramas that came from Shakespeare. In school for my Form 6 I still remember doing Hamlet for my English Literature paper and this is what I remember most from it;

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them?—To die,—to sleep,—

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to,—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d. To die,—to sleep;—

To sleep: perchance to dream:—ay, there’s the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despis’d love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would these fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,—

The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns,—puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought;

And enterprises of great pith and moment,

With this regard, their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action

Act III, scene i (58–90)

This is most probably one of the most remembered and powerful speech in the English language today. Hamlet's most logical and powerful examination of the theme of the moral legitimacy of suicide in an unbearably painful world, it touches on several of the other important themes of the play. Hamlet poses the problem of whether to commit suicide as a logical question: “To be, or not to be,” that is, to live or not to live. He then weighs the moral ramifications of living and dying. Is it nobler to suffer life, “[t]he slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” passively or to actively seek to end one’s suffering? He compares death to sleep and thinks of the end to suffering, pain, and uncertainty it might bring, “[t]he heartache, and the thousand natural shocks / That flesh is heir to.” Based on this metaphor, he decides that suicide is a desirable course of action, “a consummation / Devoutly to be wished.” But, as the religious word “devoutly” signifies, there is more to the question, namely, what will happen in the afterlife. Hamlet immediately realizes as much, and he reconfigures his metaphor of sleep to include the possibility of dreaming; he says that the dreams that may come in the sleep of death are daunting, that they “must give us pause.”

He then decides that the uncertainty of the afterlife, which is intimately related to the theme of the difficulty of attaining truth in a spiritually ambiguous world, is essentially what prevents all of humanity from committing suicide to end the pain of life. He outlines a long list of the miseries of experience, ranging from lovesickness to hard work to political oppression, and asks who would choose to bear those miseries if he could bring himself peace with a knife, “[w]hen he himself might his quietus make / With a bare bodkin?” He answers himself again, saying no one would choose to live, except that “the dread of something after death” makes people submit to the suffering of their lives rather than go to another state of existence which might be even more miserable. The dread of the afterlife, Hamlet concludes, leads to excessive moral sensitivity that makes action impossible: “conscience does make cowards of us all . . . thus the native hue of resolution / Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought.”

In this way, this speech connects many of the play’s main themes, including the idea of suicide and death, the difficulty of knowing the truth in a spiritually ambiguous universe, and the connection between thought and action. In addition to its crucial thematic content, this speech is important for what it reveals about the quality of Hamlet’s mind. His deeply passionate nature is complemented by a relentlessly logical intellect, which works furiously to find a solution to his misery. He has turned to religion and found it inadequate to help him either kill himself or resolve to kill Claudius. Here, he turns to a logical philosophical inquiry and finds it equally frustrating.

This particular soliloquy moved me as at the time I had been going through what I would call a 'dark shadow of gloom cast upon my life' time as Hamlet talks about the contemplation of suicide and death. And it still does even today even though my life is not so dark and gloomy anymore because of the use of such language to describe conflict and pain in a character.

Works Cited:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drama

http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/hamlet/quotes.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamlet

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action" (Classical Greek: δρᾶμα, drama), which is derived from the verb meaning "to do" or "to act" (Classical Greek: δράω, draō). The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception. The early modern tragedy Hamlet (1601) by Shakespeare and the classical Athenian tragedy Oedipus the King (c. 429 BCE) by Sophocles are among the masterpieces of the art of drama. A modern example is Long Day's Journey into Night by Eugene O’Neill (1956).

The two masks associated with drama represent the traditional generic division between comedy and tragedy. They are symbols of the ancient Greek Muses, Thalia and Melpomene. Thalia was the Muse of comedy (the laughing face), while Melpomene was the Muse of tragedy (the weeping face). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been contrasted with the epic and the lyrical modes ever since Aristotle's Poetics (c. 335 BCE)—the earliest work of dramatic theory.

Forms of Drama:

Opera

Western opera is a dramatic art form, which arose during the Renaissance in an attempt to revive the classical Greek drama tradition in which both music and theatre were combined. Being strongly intertwined with western classical music, the opera has undergone enormous changes in the past four centuries and it is an important form of theatre until this day. Noteworthy is the huge influence of the German 19th-century composer Richard Wagner on the opera tradition. In his view, there was no proper balance between music and theatre in the operas of his time, because the music seemed to be more important than the dramatic aspects in these works. To restore the connection with the traditional Greek drama, he entirely renewed the operatic format, and to emphasize the equal importance of music and drama in these new works, he called them "music dramas".

Chinese opera has seen a more conservative development over a somewhat longer period of time.

Pantomime

These stories follow in the tradition of fables and folk tales. Usually there is a lesson learned, and with some help from the audience, the hero/heroine saves the day. This kind of play uses stock characters seen in masque and again commedia dell'arte, these characters include the villain (doctore), the clown/servant (Arlechino/Harlequin/buttons), the lovers etc. These plays usually have an emphasis on moral dilemmas, and good always triumphs over evil, this kind of play is also very entertaining making it a very effective way of reaching many people.

Creative drama

Creative drama includes dramatic activities and games used primarily in educational settings with children. Its roots in the United States began in the early 1900s. Winifred Ward is considered to be the founder of creative drama in education, establishing the first academic use of drama in Evanston, Illinois.

My favourite playright

William Shakespeare was one of the first playrights I had began reading as a young child. I was introduced to classics like Romeo and Juliet and a little bit of King Henry VIII (the simplified version) while I was in primary school. Later I began reading more and more of his works that was not simplified and realized I had a love for the medieval dramas that came from Shakespeare. In school for my Form 6 I still remember doing Hamlet for my English Literature paper and this is what I remember most from it;

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them?—To die,—to sleep,—

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to,—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d. To die,—to sleep;—

To sleep: perchance to dream:—ay, there’s the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despis’d love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would these fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,—

The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns,—puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought;

And enterprises of great pith and moment,

With this regard, their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action

Act III, scene i (58–90)

This is most probably one of the most remembered and powerful speech in the English language today. Hamlet's most logical and powerful examination of the theme of the moral legitimacy of suicide in an unbearably painful world, it touches on several of the other important themes of the play. Hamlet poses the problem of whether to commit suicide as a logical question: “To be, or not to be,” that is, to live or not to live. He then weighs the moral ramifications of living and dying. Is it nobler to suffer life, “[t]he slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” passively or to actively seek to end one’s suffering? He compares death to sleep and thinks of the end to suffering, pain, and uncertainty it might bring, “[t]he heartache, and the thousand natural shocks / That flesh is heir to.” Based on this metaphor, he decides that suicide is a desirable course of action, “a consummation / Devoutly to be wished.” But, as the religious word “devoutly” signifies, there is more to the question, namely, what will happen in the afterlife. Hamlet immediately realizes as much, and he reconfigures his metaphor of sleep to include the possibility of dreaming; he says that the dreams that may come in the sleep of death are daunting, that they “must give us pause.”

He then decides that the uncertainty of the afterlife, which is intimately related to the theme of the difficulty of attaining truth in a spiritually ambiguous world, is essentially what prevents all of humanity from committing suicide to end the pain of life. He outlines a long list of the miseries of experience, ranging from lovesickness to hard work to political oppression, and asks who would choose to bear those miseries if he could bring himself peace with a knife, “[w]hen he himself might his quietus make / With a bare bodkin?” He answers himself again, saying no one would choose to live, except that “the dread of something after death” makes people submit to the suffering of their lives rather than go to another state of existence which might be even more miserable. The dread of the afterlife, Hamlet concludes, leads to excessive moral sensitivity that makes action impossible: “conscience does make cowards of us all . . . thus the native hue of resolution / Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought.”

In this way, this speech connects many of the play’s main themes, including the idea of suicide and death, the difficulty of knowing the truth in a spiritually ambiguous universe, and the connection between thought and action. In addition to its crucial thematic content, this speech is important for what it reveals about the quality of Hamlet’s mind. His deeply passionate nature is complemented by a relentlessly logical intellect, which works furiously to find a solution to his misery. He has turned to religion and found it inadequate to help him either kill himself or resolve to kill Claudius. Here, he turns to a logical philosophical inquiry and finds it equally frustrating.

This particular soliloquy moved me as at the time I had been going through what I would call a 'dark shadow of gloom cast upon my life' time as Hamlet talks about the contemplation of suicide and death. And it still does even today even though my life is not so dark and gloomy anymore because of the use of such language to describe conflict and pain in a character.

Works Cited:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drama

http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/hamlet/quotes.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamlet

Monday, 7 October 2013

What is Poetry?

What is Poetry?

Poetry (from the Greek poiesis — ποίησις — meaning a "making")

is a form of art that is self expressed by using meter, rhyme and other forms of poetry. It dates back to the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. In ancient times, poetry was not written down but was orally passed on from generation to the next generation.

Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest different interpretation to words, or to evoke emotive responses. Devices such as alliteration, onomatopoeia and rhythm are sometimes used to achieve musical or incantatory effects. The use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations.

Most poetry is specific to culture and genres where the reader is able to identify it and respond based on the characteristics of the poem. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz and Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition, playing with and testing, among others, the principle of euphony itself, sometimes altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm. In today's increasingly globalized world, poets often adapt forms, styles and techniques from diverse cultures and languages.

These are some of the forms of poetry used when composing poems:

Acrostic

A poem in which the first letter of each line spells out a word, name, or phrase when read vertically. See Lewis Carroll’s “A Boat beneath a Sunny Sky.”

Alexandrine

In English, a 12-syllable iambic line adapted from French heroic verse. The last line of each stanza in Thomas Hardy’s “The Convergence of the Twain” and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “To a Skylark” is an alexandrine.

Anagram

A word spelled out by rearranging the letters of another word; for example, “The teacher gapes at the mounds of exam pages lying before her.”

Aubade

A love poem or song welcoming or lamenting the arrival of the dawn. The form originated in medieval France. See John Donne’s “The Sun Rising” and Louise Bogan’s “Leave-Taking.” Browse more aubade poems.

Ballad

A popular narrative song passed down orally. In the English tradition, it usually follows a form of rhymed (abcb) quatrains alternating four-stress and three-stress lines. Folk (or traditional) ballads are anonymous and recount tragic, comic, or heroic stories with emphasis on a central dramatic event; examples include “Barbara Allen” and “John Henry.” Beginning in the Renaissance, poets have adapted the conventions of the folk ballad for their own original compositions. Examples of this “literary” ballad form include John Keats’s “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” Thomas Hardy’s “During Wind and Rain,” and Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee.”

Ballade

An Old French verse form that usually consists of three eight-line stanzas and a four-line envoy, with a rhyme scheme of ababbcbc bebc. The last line of the first stanza is repeated at the end of subsequent stanzas and the envoy. See Hilaire Belloc’s “Ballade of Modest Confession” and Algernon Charles Swinburne’s translation of François Villon’s “Ballade des Pendus” (Ballade of the Hanged).

Canto

A long subsection of an epic or long narrative poem, such as Dante Alighieri’s Commedia (The Divine Comedy), first employed in English by Edmund Spenser in The Faerie Queene. Other examples include Lord Byron’s Don Juan and Ezra Pound’s Cantos.

Canzone

Literally “song” in Italian, the canzone is a lyric poem originating in medieval Italy and France and usually consisting of hendecasyllabic lines with end-rhyme. The canzone influenced the development of the sonnet.

Carol

A hymn or poem often sung by a group, with an individual taking the changing stanzas and the group taking the burden or refrain. See Robert Southwell’s “The Burning Babe”. Many traditional Christmas songs are carols, such as “I Saw Three Ships” and “The Twelve Days of Christmas.”

Concrete poetry

Verse that emphasizes nonlinguistic elements in its meaning, such as a typeface that creates a visual image of the topic. Examples include George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” and “The Altar” and George Starbuck’s “Poem in the Shape of a Potted Christmas Tree”. Browse more concrete poems.

Couplet

A pair of successive rhyming lines, usually of the same length. A couplet is “closed” when the lines form a bounded grammatical unit like a sentence (see Dorothy Parker’s “Interview”: “The ladies men admire, I’ve heard, /Would shudder at a wicked word.”). The “heroic couplet” is written in iambic pentameter and features prominently in the work of 17th- and 18th-century didactic and satirical poets such as Alexander Pope: “Some have at first for wits, then poets pass’d, /Turn’d critics next, and proved plain fools at last.” t.

Dirge

A brief hymn or song of lamentation and grief; it was typically composed to be performed at a funeral. In lyric poetry, a dirge tends to be shorter and less meditative than an elegy. See Christina Rossetti’s “A Dirge” and Sir Philip Sidney’s “Ring Out Your Bells.”

Doggerel

Bad verse traditionally characterized by clichés, clumsiness, and irregular meter. It is often unintentionally humorous. The “giftedly bad” William McGonagall was an accomplished doggerelist, as demonstrated in “The Tay Bridge Disaster”:

It must have been an awful sight,

To witness in the dusky moonlight,

While the Storm Fiend did laugh, and angry did bray,

Along the Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay,

Oh! ill-fated Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay,

I must now conclude my lay

By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay,

That your central girders would not have given way,

At least many sensible men do say,

Had they been supported on each side with buttresses,

At least many sensible men confesses,

For the stronger we our houses do build,

The less chance we have of being killed.

Dramatic monologue

A poem in which an imagined speaker addresses a silent listener, usually not the reader. Examples include Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and Ai’s “Killing Floor.” A lyric may also be addressed to someone, but it is short and songlike and may appear to address either the reader or the poet. Browse more dramatic monologue poems.

Elegy

In traditional English poetry, it is often a melancholy poem that laments its subject’s death but ends in consolation. Examples include John Milton’s “Lycidas”; Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam”; and Walt Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd.” More recently, Peter Sacks has elegized his father in “Natal Command,” and Mary Jo Bang has written “You Were You Are Elegy” and other poems for her son. In the 18th century the “elegiac stanza” emerged, though its use has not been exclusive to elegies. It is a quatrain with the rhyme scheme ABAB written in iambic pentameter. Browse more elegies.

Epic

A long narrative poem in which a heroic protagonist engages in an action of great mythic or historical significance. Notable English epics include Beowulf, Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (which follows the virtuous exploits of 12 knights in the service of the mythical King Arthur), and John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which dramatizes Satan’s fall from Heaven and humankind’s subsequent alienation from God in the Garden of Eden. Browse more epics.

Epigram

A pithy, often witty, poem. See Walter Savage Landor’s “Dirce,” [link to archived poem] Ben Jonson’s “On Gut,” [link to archived poem] or much of the work of J.V. Cunningham [link to poet page]:

This Humanist whom no beliefs constrained

Grew so broad-minded he was scatter-brained.

Epistle

A letter in verse, usually addressed to a person close to the writer. Its themes may be moral and philosophical, or intimate and sentimental. Alexander Pope favored the form; see his “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot,” in which the poet addresses a physician in his social circle. The epistle peaked in popularity in the 18th century, though Lord Byron and Robert Browning composed several in the next century; see Byron’s “Epistle to Augusta.” Less formal, more conversational versions of the epistle can be found in contemporary lyric poetry; see Hayden Carruth’s “The Afterlife: Letter to Sam Hamill” or “Dear Mr. Fanelli” by Charles Bernstein. Browse more epistles.

Epitaph

A short poem intended for (or imagined as) an inscription on a tombstone and often serving as a brief elegy. See Robert Herrick’s “Upon a Child That Died” and “Upon Ben Jonson”; Ben Jonson’s “Epitaph on Elizabeth, L. H.”; and “Epitaph for a Romantic Woman” by Louise Bogan.

Epithalamion

A lyric poem in praise of Hymen (the Greek god of marriage), an epithalamion often blesses a wedding and in modern times is often read at the wedding ceremony or reception. See Edmund Spenser’s “Epithalamion.” Browse more epithalamions.

Fixed and unfixed forms

Poems that have a set number of lines, rhymes, and/or metrical arrangements per line. Browse all terms related to forms, including alcaics, alexandrine, aubade, ballad, ballade, carol, concrete poetry, double dactyl, dramatic monologue, eclogue, elegy, epic, epistle, epithalamion, free verse, haiku, heroic couplet, limerick, madrigal, mock epic, ode, ottava rima, pastoral, quatrain, renga, rondeau, rondel, sestina, sonnet, Spenserian stanza, tanka, tercet, terza rima, and villanelle.

Free verse

Nonmetrical, nonrhyming lines that closely follow the natural rhythms of speech. A regular pattern of sound or rhythm may emerge in free-verse lines, but the poet does not adhere to a metrical plan in their composition. Matthew Arnold and Walt Whitman explored the possibilities of nonmetrical poetry in the 19th century. Since the early 20th century, the majority of published lyric poetry has been written in free verse. See the work of William Carlos Williams, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and H.D. Browse more free-verse poems.

Ghazal

(Pronounciation: “guzzle”) Originally an Arabic verse form dealing with loss and romantic love, medieval Persian poets embraced the ghazal, eventually making it their own. Consisting of syntactically and grammatically complete couplets, the form also has an intricate rhyme scheme. Each couplet ends on the same word or phrase (the radif), and is preceded by the couplet’s rhyming word (the qafia, which appears twice in the first couplet). The last couplet includes a proper name, often of the poet’s. In the Persian tradition, each couplet was of the same meter and length, and the subject matter included both erotic longing and religious belief or mysticism. English-language poets who have composed in the form include Adrienne Rich, John Hollander, and Agha Shahid Ali; see Ali’s “Tonight” and Patricia Smith’s “Hip-Hop Ghazal.”

Haiku (or hokku)

A Japanese verse form of three unrhyming lines in five, seven, and five syllables. It creates a single, memorable image, as in these lines by Kobayashi Issa, translated by Jane Hirshfield:

On a branch

floating downriver

a cricket, singing.

(In translating from Japanese to English, Hirshfield compresses the number of syllables.)

See also “Three Haiku, Two Tanka” by Philip Appleman and Robert Hass’s “After the Gentle Poet Kobayashi Issa.” The Imagist poets of the early 20th century, including Ezra Pound and H.D., showed appreciation for the form’s linguistic and sensory economy; Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” embodies the spirit of haiku.

Hymn

A poem praising God or the divine, often sung. In English, the most popular hymns were written between the 17th and 19th centuries. See Isaac Watts’s “Our God, Our Help,” Charles Wesley’s “My God! I Know, I Feel Thee Mine,” and “Thou Hidden Love of God” by John Wesley.

Lament

Any poem expressing deep grief, usually at the death of a loved one or some other loss. Related to elegy and the dirge. See “A Lament” by Percy Bysshe Shelley; Thom Gunn’s “Lament”; and Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Lament.”

Landays

A form of folk poetry from Afghanistan. Meant to be recited or sung aloud, and frequently anonymous, the form is a couplet comprised of 22 syllables. The first line has 9 syllables and the second line 13 syllables. Landays end on “ma” or “na” sounds and treat themes such as love, grief, homeland, war, and separation. See Eliza Griswold’s extensive reporting on the form in the June 2013 issue of Poetry, in which she explains how the form was created by and for the more than 20 million Pashtun women who span the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Light verse

Whimsical poems taking forms such as limericks, nonsense poems, and double dactyls. See Edward Lear’s “The Owl and the Pussy-Cat” and Lewis Carroll’s “The Walrus and the Carpenter.” Other masters of light verse include Dorothy Parker, G.K. Chesterton, John Hollander, and Wendy Cope.

Limerick

A fixed light-verse form of five generally anapestic lines rhyming AABBA. Edward Lear, who popularized the form, fused the third and fourth lines into a single line with internal rhyme. Limericks are traditionally bawdy or just irreverent; see “A Young Lady of Lynn” or Lear’s “There was an Old Man with a Beard.” Browse more limericks.

Lyric

Originally a composition meant for musical accompaniment. The term refers to a short poem in which the poet, the poet’s persona, or another speaker expresses personal feelings. See Robert Herrick’s “To Anthea, who May Command Him Anything,” John Clare’s “I Hid My Love,” Louise Bogan’s “Song for the Last Act,” or Louise Glück’s “Vita Nova.”

Madrigal

A song or short lyric poem intended for multiple singers. Originating in 14th-century Italy, it became popular in England in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. It has no fixed metrical requirements. See “Rosalind’s Madrigal” by Thomas Lodge.

.

Ode

A formal, often ceremonious lyric poem that addresses and often celebrates a person, place, thing, or idea. Its stanza forms vary. The Greek or Pindaric (Pindar, ca. 552–442 B.C.E.) ode was a public poem, usually set to music, that celebrated athletic victories. (See Stephen Burt’s article “And the Winner Is . . . Pindar!”) English odes written in the Pindaric tradition include Thomas Gray’s “The Progress of Poesy: A Pindaric Ode” and William Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Reflections of Early Childhood.” Horatian odes, after the Latin poet Horace (65–8 B.C.E.), were written in quatrains in a more philosophical, contemplative manner; see Andrew Marvell’s “Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland.” The Sapphic ode consists of quatrains, three 11-syllable lines, and a final five-syllable line, unrhyming but with a strict meter. See Algernon Charles Swinburne’s “Sapphics.”

The odes of the English Romantic poets vary in stanza form. They often address an intense emotion at the onset of a personal crisis (see Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Dejection: An Ode,”) or celebrate an object or image that leads to revelation (see John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” and “To Autumn”). Browse more odes.

Ottava rima

Originally an Italian stanza of eight 11-syllable lines, with a rhyme scheme of ABABABCC. Sir Thomas Wyatt introduced the form in English, and Lord Byron adapted it to a 10-syllable line for his mock-epic Don Juan. W.B. Yeats used it for “Among School Children” and “Sailing to Byzantium.

Palinode

An ode or song that retracts or recants what the poet wrote in a previous poem. For instance, Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales ends with a retraction, in which he apologizes for the work’s “worldly vanitees” and sinful contents.

Pantoum

A Malaysian verse form adapted by French poets and occasionally imitated in English. It comprises a series of quatrains, with the second and fourth lines of each quatrain repeated as the first and third lines of the next. The second and fourth lines of the final stanza repeat the first and third lines of the first stanza. See A.E. Stallings’s “Another Lullaby for Insomniacs.”

Prose poem

A prose composition that, while not broken into verse lines, demonstrates other traits such as symbols, metaphors, and other figures of speech common to poetry. See Amy Lowell’s “Bath,” “Metals Metals” by Russell Edson, “Information” by David Ignatow, and Harryette Mullen’s “[Kills bugs dead.]” Browse more prose poems.

Quatrain

A four-line stanza, rhyming

-ABAC or ABCB (known as unbounded or ballad quatrain), as in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

-AABB (a double couplet); see A.E. Housman’s “To an Athlete Dying Young.”

-ABAB (known as interlaced, alternate, or heroic), as in Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” or “Sadie and Maud” by Gwendolyn Brooks.

-ABBA (known as envelope or enclosed), as in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” or John Ciardi’s “Most Like an Arch This Marriage.”

-AABA, the stanza of Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.”

.

Refrain

A phrase or line repeated at intervals within a poem, especially at the end of a stanza. See the refrain “jump back, honey, jump back” in Paul Lawrence Dunbar’s “A Negro Love Song” or “return and return again” in James Laughlin’s “O Best of All Nights, Return and Return Again.” Browse poems with a refrain.

Rhyme royal (rime royale)

A stanza of seven 10-syllable lines, rhyming ABABBCC, popularized by Geoffrey Chaucer and termed “royal” because his imitator, James I of Scotland, employed it in his own verse. In addition to Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, see Sir Thomas Wyatt’s “They flee from me” and William Wordsworth’s “Resolution and Independence.”

Romance

French in origin, a genre of long narrative poetry about medieval courtly culture and secret love. It triumphed in English with tales of chivalry such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Knight’s Tale” and Troilus and Criseyde.

Rondeau

Originating in France, a mainly octosyllabic poem consisting of between 10 and 15 lines and three stanzas. It has only two rhymes, with the opening words used twice as an unrhyming refrain at the end of the second and third stanzas. The 10-line version rhymes ABBAABc ABBAc (where the lower-case “c” stands for the refrain). The 15-line version often rhymes AABBA AABc AABAc. Geoffrey Chaucer’s “Now welcome, summer” at the close of The Parlement of Fowls is an example of a 13-line rondeau.

A rondeau redoublé consists of six quatrains using two rhymes. The first quatrain consists of four refrain lines that are used, in sequence, as the last lines of the next four quatrains, and a phrase from the first refrain is repeated as a tail at the end of the final stanza. See Dorothy Parker’s “Roudeau Redoublé (and Scarcely Worth the Trouble at That).”

Sonnet

A 14-line poem with a variable rhyme scheme originating in Italy and brought to England by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, earl of Surrey in the 16th century. Literally a “little song,” the sonnet traditionally reflects upon a single sentiment, with a clarification or “turn” of thought in its concluding lines.

The Petrarchan sonnet, perfected by the Italian poet Petrarch, divides the 14 lines into two sections: an eight-line stanza (octave) rhyming ABBAABBA, and a six-line stanza (sestet) rhyming CDCDCD or CDEEDE. John Milton’s “When I Consider How my Light Is Spent” and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “How Do I Love Thee” employ this form.

The Italian sonnet is an English variation on the traditional Petrarchan version. The octave’s rhyme scheme is preserved, but the sestet rhymes CDDCEE. See Thomas Wyatt’s “Whoso List to Hunt, I Know Where Is an Hind” and John Donne’s “If Poisonous Minerals, and If That Tree.”

Wyatt and Surrey developed the English (or Shakespearean) sonnet, which condenses the 14 lines into one stanza of three quatrains and a concluding couplet, with a rhyme scheme of ABABCDCDEFEFGG (though poets have frequently varied this scheme; see Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem for Doomed Youth”). George Herbert’s “Love (II),” Claude McKay’s “America,” and Molly Peacock’s “Altruism” are English sonnets.

These three types have given rise to many variations, including:

-The caudate sonnet, which adds codas or tails to the 14-line poem. See Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “That Nature Is a Heraclitean Fire.”

-The curtal sonnet, a shortened version devised by Gerard Manley Hopkins that maintains the proportions of the Italian form, substituting two six-stress tercets for two quatrains in the octave (rhyming ABC ABC), and four and a half lines for the sestet (rhyming DEBDE), also six-stress except for the final three-stress line. See his poem “Pied Beauty.”

-The sonnet redoublé, also known as a crown of sonnets, is composed of 15 sonnets that are linked by the repetition of the final line of one sonnet as the initial line of the next, and the final line of that sonnet as the initial line of the previous; the last sonnet consists of all the repeated lines of the previous 14 sonnets, in the same order in which they appeared. Marilyn Nelson’s A Wreath for Emmett Till is a contemporary example.

-A sonnet sequence is a group of sonnets sharing the same subject matter and sometimes a dramatic situation and persona. See George Meredith’s Modern Love sequence, Sir Philip Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella, Rupert Brooke’s 1914 sequence, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese.

-The Spenserian sonnet is a 14-line poem developed by Edmund Spenser in his Amoretti, that varies the English form by interlocking the three quatrains (ABAB BCBC CDCD EE).

-The stretched sonnet is extended to 16 or more lines, such as those in George Meredith’s sequence Modern Love.

-A submerged sonnet is tucked into a longer poetic work; see lines 235-48 of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.”

Stanza

A grouping of lines separated from others in a poem. In modern free verse, the stanza, like a prose paragraph, can be used to mark a shift in mood, time, or thought.

Syllabic verse

Poetry whose meter is determined by the total number of syllables per line, rather than the number of stresses. Marianne Moore’s poetry is mostly syllabic. Other examples include Thomas Nashe’s “Adieu, farewell earth’s bliss” and Dylan Thomas’s “Poem in October.” Browse more poems in syllabic verse.

Tercet

A poetic unit of three lines, rhymed or unrhymed. Thomas Hardy’s “The Convergence of the Twain” rhymes AAA BBB; Ben Jonson’s “On Spies” is a three-line poem rhyming AAA; and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind” is written in terza rima form. Examples of poems in unrhymed tercets include Wallace Stevens’s “The Snow Man” and David Wagoner’s “For a Student Sleeping in a Poetry Workshop.”

Terza rima

An Italian stanzaic form, used most notably by Dante Alighieri in Commedia (The Divine Comedy), consisting of tercets with interwoven rhymes (ABA BCB DED EFE, and so on). A concluding couplet rhymes with the penultimate line of the last tercet. See Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind,” Derek Walcott’s “The Bounty,” and Omeros, and Jacqueline Osherow’s “Autumn Psalm.”

Triolet

An eight-line stanza having just two rhymes and repeating the first line as the fourth and seventh lines, and the second line as the eighth. See Sandra McPherson’s “Triolet” or “Triolets in the Argolid” by Rachel Hadas.

Verse

As a mass noun, poetry in general; as a regular noun, a line of poetry. Typically used to refer to poetry that possesses more formal qualities.

Verse paragraph

A group of verse lines that make up a single rhetorical unit. In longer poems, the first line is often indented, like a paragraph in prose. The long narrative passages of John Milton’s Paradise Lost are verse paragraphs. The titled sections of Robert Pinsky’s “Essay on Psychiatrists” demarcate shifts in focus and argument much as prose paragraphs would. A shorter lyric poem, even when broken into stanzas, could be considered a single verse paragraph, insofar as it expresses a unified mood or thought; see Gail Mazur’s “Evening.”

Villanelle

A French verse form consisting of five three-line stanzas and a final quatrain, with the first and third lines of the first stanza repeating alternately in the following stanzas. These two refrain lines form the final couplet in the quatrain. See “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas, Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” and Edwin Arlington Robinson’s “The House on the Hill.”

Cited from:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poetry

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/

Poetry (from the Greek poiesis — ποίησις — meaning a "making")

is a form of art that is self expressed by using meter, rhyme and other forms of poetry. It dates back to the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. In ancient times, poetry was not written down but was orally passed on from generation to the next generation.

Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest different interpretation to words, or to evoke emotive responses. Devices such as alliteration, onomatopoeia and rhythm are sometimes used to achieve musical or incantatory effects. The use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations.

Most poetry is specific to culture and genres where the reader is able to identify it and respond based on the characteristics of the poem. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz and Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition, playing with and testing, among others, the principle of euphony itself, sometimes altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm. In today's increasingly globalized world, poets often adapt forms, styles and techniques from diverse cultures and languages.

These are some of the forms of poetry used when composing poems:

Acrostic

A poem in which the first letter of each line spells out a word, name, or phrase when read vertically. See Lewis Carroll’s “A Boat beneath a Sunny Sky.”

Alexandrine

In English, a 12-syllable iambic line adapted from French heroic verse. The last line of each stanza in Thomas Hardy’s “The Convergence of the Twain” and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “To a Skylark” is an alexandrine.

Anagram

A word spelled out by rearranging the letters of another word; for example, “The teacher gapes at the mounds of exam pages lying before her.”

Aubade

A love poem or song welcoming or lamenting the arrival of the dawn. The form originated in medieval France. See John Donne’s “The Sun Rising” and Louise Bogan’s “Leave-Taking.” Browse more aubade poems.

Ballad

A popular narrative song passed down orally. In the English tradition, it usually follows a form of rhymed (abcb) quatrains alternating four-stress and three-stress lines. Folk (or traditional) ballads are anonymous and recount tragic, comic, or heroic stories with emphasis on a central dramatic event; examples include “Barbara Allen” and “John Henry.” Beginning in the Renaissance, poets have adapted the conventions of the folk ballad for their own original compositions. Examples of this “literary” ballad form include John Keats’s “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” Thomas Hardy’s “During Wind and Rain,” and Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee.”

Ballade

An Old French verse form that usually consists of three eight-line stanzas and a four-line envoy, with a rhyme scheme of ababbcbc bebc. The last line of the first stanza is repeated at the end of subsequent stanzas and the envoy. See Hilaire Belloc’s “Ballade of Modest Confession” and Algernon Charles Swinburne’s translation of François Villon’s “Ballade des Pendus” (Ballade of the Hanged).

Canto

A long subsection of an epic or long narrative poem, such as Dante Alighieri’s Commedia (The Divine Comedy), first employed in English by Edmund Spenser in The Faerie Queene. Other examples include Lord Byron’s Don Juan and Ezra Pound’s Cantos.

Canzone

Literally “song” in Italian, the canzone is a lyric poem originating in medieval Italy and France and usually consisting of hendecasyllabic lines with end-rhyme. The canzone influenced the development of the sonnet.

Carol

A hymn or poem often sung by a group, with an individual taking the changing stanzas and the group taking the burden or refrain. See Robert Southwell’s “The Burning Babe”. Many traditional Christmas songs are carols, such as “I Saw Three Ships” and “The Twelve Days of Christmas.”

Concrete poetry

Verse that emphasizes nonlinguistic elements in its meaning, such as a typeface that creates a visual image of the topic. Examples include George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” and “The Altar” and George Starbuck’s “Poem in the Shape of a Potted Christmas Tree”. Browse more concrete poems.

Couplet

A pair of successive rhyming lines, usually of the same length. A couplet is “closed” when the lines form a bounded grammatical unit like a sentence (see Dorothy Parker’s “Interview”: “The ladies men admire, I’ve heard, /Would shudder at a wicked word.”). The “heroic couplet” is written in iambic pentameter and features prominently in the work of 17th- and 18th-century didactic and satirical poets such as Alexander Pope: “Some have at first for wits, then poets pass’d, /Turn’d critics next, and proved plain fools at last.” t.

Dirge

A brief hymn or song of lamentation and grief; it was typically composed to be performed at a funeral. In lyric poetry, a dirge tends to be shorter and less meditative than an elegy. See Christina Rossetti’s “A Dirge” and Sir Philip Sidney’s “Ring Out Your Bells.”

Doggerel

Bad verse traditionally characterized by clichés, clumsiness, and irregular meter. It is often unintentionally humorous. The “giftedly bad” William McGonagall was an accomplished doggerelist, as demonstrated in “The Tay Bridge Disaster”:

It must have been an awful sight,

To witness in the dusky moonlight,

While the Storm Fiend did laugh, and angry did bray,

Along the Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay,

Oh! ill-fated Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay,

I must now conclude my lay

By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay,

That your central girders would not have given way,

At least many sensible men do say,

Had they been supported on each side with buttresses,

At least many sensible men confesses,

For the stronger we our houses do build,

The less chance we have of being killed.

Dramatic monologue

A poem in which an imagined speaker addresses a silent listener, usually not the reader. Examples include Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and Ai’s “Killing Floor.” A lyric may also be addressed to someone, but it is short and songlike and may appear to address either the reader or the poet. Browse more dramatic monologue poems.

Elegy

In traditional English poetry, it is often a melancholy poem that laments its subject’s death but ends in consolation. Examples include John Milton’s “Lycidas”; Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam”; and Walt Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd.” More recently, Peter Sacks has elegized his father in “Natal Command,” and Mary Jo Bang has written “You Were You Are Elegy” and other poems for her son. In the 18th century the “elegiac stanza” emerged, though its use has not been exclusive to elegies. It is a quatrain with the rhyme scheme ABAB written in iambic pentameter. Browse more elegies.

Epic

A long narrative poem in which a heroic protagonist engages in an action of great mythic or historical significance. Notable English epics include Beowulf, Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (which follows the virtuous exploits of 12 knights in the service of the mythical King Arthur), and John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which dramatizes Satan’s fall from Heaven and humankind’s subsequent alienation from God in the Garden of Eden. Browse more epics.

Epigram

A pithy, often witty, poem. See Walter Savage Landor’s “Dirce,” [link to archived poem] Ben Jonson’s “On Gut,” [link to archived poem] or much of the work of J.V. Cunningham [link to poet page]:

This Humanist whom no beliefs constrained

Grew so broad-minded he was scatter-brained.

Epistle

A letter in verse, usually addressed to a person close to the writer. Its themes may be moral and philosophical, or intimate and sentimental. Alexander Pope favored the form; see his “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot,” in which the poet addresses a physician in his social circle. The epistle peaked in popularity in the 18th century, though Lord Byron and Robert Browning composed several in the next century; see Byron’s “Epistle to Augusta.” Less formal, more conversational versions of the epistle can be found in contemporary lyric poetry; see Hayden Carruth’s “The Afterlife: Letter to Sam Hamill” or “Dear Mr. Fanelli” by Charles Bernstein. Browse more epistles.

Epitaph

A short poem intended for (or imagined as) an inscription on a tombstone and often serving as a brief elegy. See Robert Herrick’s “Upon a Child That Died” and “Upon Ben Jonson”; Ben Jonson’s “Epitaph on Elizabeth, L. H.”; and “Epitaph for a Romantic Woman” by Louise Bogan.

Epithalamion

A lyric poem in praise of Hymen (the Greek god of marriage), an epithalamion often blesses a wedding and in modern times is often read at the wedding ceremony or reception. See Edmund Spenser’s “Epithalamion.” Browse more epithalamions.

Fixed and unfixed forms

Poems that have a set number of lines, rhymes, and/or metrical arrangements per line. Browse all terms related to forms, including alcaics, alexandrine, aubade, ballad, ballade, carol, concrete poetry, double dactyl, dramatic monologue, eclogue, elegy, epic, epistle, epithalamion, free verse, haiku, heroic couplet, limerick, madrigal, mock epic, ode, ottava rima, pastoral, quatrain, renga, rondeau, rondel, sestina, sonnet, Spenserian stanza, tanka, tercet, terza rima, and villanelle.

Free verse

Nonmetrical, nonrhyming lines that closely follow the natural rhythms of speech. A regular pattern of sound or rhythm may emerge in free-verse lines, but the poet does not adhere to a metrical plan in their composition. Matthew Arnold and Walt Whitman explored the possibilities of nonmetrical poetry in the 19th century. Since the early 20th century, the majority of published lyric poetry has been written in free verse. See the work of William Carlos Williams, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and H.D. Browse more free-verse poems.

Ghazal

(Pronounciation: “guzzle”) Originally an Arabic verse form dealing with loss and romantic love, medieval Persian poets embraced the ghazal, eventually making it their own. Consisting of syntactically and grammatically complete couplets, the form also has an intricate rhyme scheme. Each couplet ends on the same word or phrase (the radif), and is preceded by the couplet’s rhyming word (the qafia, which appears twice in the first couplet). The last couplet includes a proper name, often of the poet’s. In the Persian tradition, each couplet was of the same meter and length, and the subject matter included both erotic longing and religious belief or mysticism. English-language poets who have composed in the form include Adrienne Rich, John Hollander, and Agha Shahid Ali; see Ali’s “Tonight” and Patricia Smith’s “Hip-Hop Ghazal.”

Haiku (or hokku)

A Japanese verse form of three unrhyming lines in five, seven, and five syllables. It creates a single, memorable image, as in these lines by Kobayashi Issa, translated by Jane Hirshfield:

On a branch

floating downriver

a cricket, singing.

(In translating from Japanese to English, Hirshfield compresses the number of syllables.)

See also “Three Haiku, Two Tanka” by Philip Appleman and Robert Hass’s “After the Gentle Poet Kobayashi Issa.” The Imagist poets of the early 20th century, including Ezra Pound and H.D., showed appreciation for the form’s linguistic and sensory economy; Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” embodies the spirit of haiku.

Hymn

A poem praising God or the divine, often sung. In English, the most popular hymns were written between the 17th and 19th centuries. See Isaac Watts’s “Our God, Our Help,” Charles Wesley’s “My God! I Know, I Feel Thee Mine,” and “Thou Hidden Love of God” by John Wesley.

Lament